Posts Tagged Essays

Life’s Messy Discomfort through the Lens of Greta Gerwig

Spoilers should be assumed for Lady Bird, Little Women, and Barbie.

I remember watching Frances Ha in the summer of 2012 and being instantly swept away by the heartfelt realism, painfully relatable comedy, and pervading sense of optimism throughout the film. It quickly became my favorite Noah Baumbach film, and I half-jokingly, half-seriously said I had either lived every scene in it or knew someone who had. While Frances Ha may not have been my first introduction to Greta Gerwig, it certainly was the first time I was aware of her as an artist as she danced through the streets of New York in glorious black and white.

Now just over a decade later, Gerwig has written several more screenplays and directed three movies of her own. Anyone who has followed any portion of my film commentary over the last five years knows that I adore Lady Bird like few other movies and possibly that I saw her Little Women five times in theaters. And Barbie has only grown tremendously in my estimation after two viewings.

With the exception of Wes Anderson, I cannot think of any auteur working today other than Gerwig who makes movies that depict an imperfect world with so much joy, hope, and love. From Lady Bird to Barbie, Gerwig has captured a recognition of the potential the world has to be good with a full awareness of how it should be in the midst of all of its shortcomings. This notion comes from Graham Greene and his writings on film criticism, and when movies can capture that sort of expression, they show an act of creation partaking in the glory of all creation. Indeed, given the Genesis-inspired themes in Barbie, it is easy to imagine Gerwig as a creator looking over her films and their views of the world and pronouncing them both good.

The goodness of the worlds depicted in Gerwig’s films shows an incredible sense of hope given the heartaches, betrayals, and ways characters can hurt one another and themselves. In a review of Frances Ha published a decade ago, Eve Tushnet wrote: “Frances herself is just a beautiful character. You get how she can be exasperating. She’s impulsive, she lets her dreams consume and threaten her real life, she’s awkward in a way which can come across as self-centered and idealistic in a way which can come across as entitled. She’s too much, consistently. But she’s also just a joy to be around.” I think it is very much worth pointing out that Frances is played by Gerwig and clearly a character created out of love and that Eve titled her review “Hope Stumbles Eternal.”

As a concise summary of what I love about all of Gerwig’s movies, I think “Hope stumbles eternal” could be applied from Lady Bird to Little Women to Barbie. Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, Jo March, and Stereotypical Barbie are three very different protagonists, but from falling out of a car to having trips to Europe taken away to getting flat feet, all of them take literal and figurative falls that open new paths to discover that aforementioned hope along with joy and love.

The first time I saw Lady Bird, the scene that delighted me the most was the musical audition where all the high school kids sang Sondheim, except for Beanie Feldstein’s Julie. It was such a delightful surprise to see and hear that many Sondheim songs as high school performers bit off more than they could chew, and it was a microcosmic way of showing the dreams and aspirations for what the world can be and the less than perfect reality. Barbie contains a similarly delightful surprise with its prologue homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the simplified and erroneous view of the Barbies, the invention of Barbie, like the obelisk in 2001, spurred humankind, specifically women, to take tremendous steps forward in progress and equality. It expresses the hopeful desires of feminism while eliciting laughs for the far the less-than-ideal reality that every viewer is aware of.

Continuing with the 2001 homage, the finale of Barbie frames the film with several Kubrick references. The dialogue between Barbie and her creator, Ruth Handler (Rhea Perlman), takes place in a white void, not dissimilar to the room at the end of 2001. In both films the protagonist is then reborn. In Barbie, right before this rebirth Barbie says that life has gotten too complicated and discomforting to go back to Barbieland. And yet, Gerwig—through Perlman’s urging Barbie to feel and through the montage of the joys and pains of life—says this discomfort and messiness is nothing to be afraid of, but something to be embraced. The final zinger that Robbie delivers after that scene is unquestionably reminiscent of the final lines in both A Clockwork Orange and Eyes Wide Shut.

How do two dystopian nightmares such as those Kubrick films (one comedy, one horror) tie into a depiction of the world as it is and as it should be? Wouldn’t those two films more accurately depict worlds that no one would want to inhabit? While the answer to that second question is yes for any non-psychopath, both Kubrick films exaggerate the dysfunction of a world where freewill is eradicated (through over-the-top comedy) and the danger of a world where fidelity is tossed aside (through creepy sexual rituals). In both cases, there is a clear acknowledgement of what is broken with a realization of how things should be different.

Barbieland itself is a brilliant inversion of patriarchy. As a means of highlighting the dysfunctional and sexist nature of a patriarchal society, showing a world where the Kens are subjugated, hold no positions of power, and exist only for the Barbies’ entertainment and companionship reveals the objectification many women have experienced in the real world, while simultaneously laughing in the face of patriarchy. Indeed, the absurd accusations of misandry from the film’s critics make it clear that the parody hit its intended mark.

For all that has been made of America Ferrera’s dramatic third act speech in Barbie, I’m surprised that almost no one (or literally no one?) has pointed out that Saoirse Ronan makes nearly the same speech toward the end of Little Women. Both speeches could be considered a sort of condensed feminist manifesto. Ferrera’s exasperated mother and Barbie lover Gloria voices the disconnect and absurd double standard of being a woman under patriarchy—thus robbing the patriarchy of its power by giving voice to that cognitive dissonance, which Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie points out to her own shock.

Near the end of Little Women, after Jo has watched one of her sisters die, lost a trip to Europe she dreamed of, rejected an offer of marriage, and had her short stories severely critiqued by a friend, she is reconsidering what to make of her life. In a similarly dramatic speech to the one in Barbie, she exclaims to Marmee: “Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty. I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for. I’m so sick of it.” Then after a beat she adds much more somberly, “But I’m so lonely.”

That following line voices the same dissonance as Ferrera’s big speech in Barbie and the less-than-ideal reality that many people often experience in life. It in no way undermines Jo’s desire for independence and dreams of being a self-sustaining writer. Jo’s happiness in a marriage only comes after she is fully happy as herself. When she agrees to end her novel with a marriage so it will sell, she quotes Amy’s earlier line that “marriage has always been an economic proposition.”

At the same time, Little Women shows loving, healthy marriages. All of them have struggles and quarrels, but the beauty of the relationships and love between the couples cannot be overlooked. As Jo suggests to Meg on her wedding day that the two of them run away and support themselves through writing and acting, Emma Watson’s response reminds Jo and the viewer of the validity of all vocations. “Just because my dreams are different than yours doesn’t mean they’re unimportant.”

Recognizing the importance of marriage and independence ultimately gives the portrayal of relationships in Little Women more depth and affection. The ability to hold two ideas as equals that society often says need to be opposites is a sign of the beauty to be found in life’s discomforting moments—both moments of joy and loneliness. Put another way, as Lawyer Barbie says, “This makes me emotional and I’m expressing it. I have no difficulty holding both logic and emotion at the same time, and it does not diminish my powers. It expands them.”

Simultaneously holding logic and emotion is not something that Ronan’s headstrong teenage Lady Bird does. Nor does her equally strong-willed mother played by Laurie Metcalf. The tempestuous relationship between mother and daughter forms most of the conflict in Lady Bird, punctuated by the ups and downs of a senior year of high school.

That central conflict along with the supporting ones is captured by the film’s prologue. Lady Bird and her mother finish college visits and complete the audio book of The Grapes of Wrath as they drive home, and the initial moment of bonding quickly turns sour as the Lady Bird’s dreams of attending an East Coast college, experiencing culture, and becoming famous jar with her mother’s practical sense of reality. Both actresses deliver Gerwig’s sharp retorts with such humor that the toxicity of the relationship could be overlooked in this scene. When Lady Bird rolls out of the moving car and breaks her arm, it should be more apparent, especially when the next cut is to a closeup of her cast with “Fuck you, Mom” written on it in tiny print.

I think the tension created from that opening sequence—which builds throughout the film via secret college applications, careless slips from boyfriends, school suspensions, and more—is one reason the ending of Lady Bird is so powerful. (Since my first viewing of Lady Bird, I have cried all fifteen or so additional times that I’ve seen it at the ending.) First and foremost, the ending of Lady Bird expresses a desire and hope for healing from abusive relationships. Secondly, it taps beautifully into the messy imperfections of the world as it is and realizes there is a better way for it to be.

It is very important to mention that Lady Bird does not absolve Laurie Metcalf’s emotionally abusive mother. Metcalf is so fantastic in the role that it becomes easy to sympathize with her character as we see an overworked mom trying the best to provide for her family and afraid of losing them. The possibility of reconciliation is brought about by mediation through Tracy Letts’ father (in an equally amazing performance). After Lady Bird receives the handwritten letters, she reaches out in response to them. (If you haven’t paused Lady Bird while watching it to read those letters, you need to do so.)

The final phone call in Lady Bird, complete with crosscuts between Metcalf and Ronan driving the same Sacramento streets, is unquestionably the greatest scene Gerwig has shot thus far. The comparison between mother and daughter, acknowledgment of the dysfunctional relationship, and depiction of the love that both of them have for each other is perfectly portrayed. It is not a moment of reconciliation, as the phone call is a voicemail and we never see where the relationship goes moving forward, but it is a first step of healing as Christine realizes that there are indissoluble bonds with her parents.

For many people who have toxic relationships with their parents, and especially for those who have gone no contact, such a scene may be very difficult to watch. I won’t deny a large part of the emotions I feel during the finale of Lady Bird stems from my own strained family relationships. However, returning to the Graham Greene quote at the beginning of this essay, Lady Bird depicts a healing that everyone should wish for regardless of whether or not it is attainable in this world. For me, the longing for that healing makes the scene just as cathartic if not more so than had that healing occurred, because the longing is what creates the happy-sad tension between what is and what should be.

As Christine walks off her first hangover after moving to New York for college, stumbling into a church reminds her of her parents and need for connection. I vividly remember my first hangover and the guilt I felt afterwards, and reaching out for a nurturing connection is a natural response. Had it not been for the letters that Christine found in her college suitcase, she would have left home without any of that nurture, and her final phone call would have come across as undeserved forgiveness for her mom. (Again, pause your Blu-ray/stream of Lady Bird and read those letters.) It is at the lowest moment of messy brokenness that Lady Bird (and all of us) turn outward to realize our interconnectedness.

As the montage that Stereotypically Barbie watches before she becomes human also shows, that interconnectedness is inherently messy, and that is a beautiful thing. Barbie also has a quintessential moment of brokenness and dejection, not dissimilar to Lady Bird’s hangover; however, that moment is responded to with an hilarious joke from Helen Mirren’s narrator.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, “that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife,” to quote Jane Austen and hat-tip another Barbie reference, and that tragedy and comedy are two sides of the same coin. Barbie’s comedic response to its protagonist hitting rock bottom is not that dissimilar from heartfelt phone call that ends Lady Bird. As Stereotypical Barbie cries that she failed the Barbies and that she has turned ugly and ordinary, Mirren states: “Note to the filmmakers: Margot Robbie is the wrong person to cast if you want to make this point.”

The difference in how we perceive ourselves after any literal or figurative fall and the reality of our inherent worth is often at odds. Mirren’s narration humorously rips an old-fashioned societal notion that everything has to go perfectly and women have to look their best to be beautiful. It builds on the earlier scene when Barbie tells an older woman who does not fit patriarchal standards of beauty that she is beautiful, and she replies, “I know it.” That self-confidence is something we should all aspire to, and given Barbie’s ending about embracing life as we are, it does not seem a stretch to say that old woman is an example of a life well lived. (Given that the woman is framed next to a recycling bin, I think there’s an obvious connection between the different stages of observing the overlooked woman recycling a bottle throughout Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy, but that may be coincidental.)

Returning to the similarity with the ending of Lady Bird, when Christine calls her parents, she is reaching out for a connection after a bad fall and accepting herself and her mom with both of their imperfections. Living into her truth as herself, it is the first time in the film that Christine uses her name and not her moniker of teen rebellion that she went by for most of the film. Like Mirren’s joke in Barbie, Ronan’s entire monologue is a statement that she and her mom are beautiful people despite the tumbles they’ve both taken. Continuing the Kieslowski similarities, the way Irene Jacob lays her hand on the tree that connects her and her double at the end of The Double Life of Veronique could be another coincidental point of comparison.

Given that Lady Bird opens with another fall, framing this story of grace with two falls—one literally out of a car and the second an emotional fall after rushing to the emergency room in a panic over first time intoxication—reflects how strongly hope stumbles eternal in the cinema of Greta Gerwig. Barbie’s transition into a real girl in acknowledgement of the imperfections of both Barbieland and the real world is an embracing of such falls. And the emotional growth of all the March sisters in Little Women is almost always juxtaposed with such falls.

In reordering the chronology of Alcott’s novel, Gerwig highlighted different aspects of the well-known story through juxtaposing specific later events with earlier ones. What Gerwig also achieved through this editing was turning the main plot of the story into a young struggling writer returning home to face the death of her younger sister, while remembering the good and bad memories they had with their family. These memories end up forming the titular novel, and as the opening quote from Alcott states: “I’ve had lots of troubles, so I write jolly tales.”

Little Women is at its heart a jolly tale of love between sisters. That does not mean it does not contain its share of troubles, since the joy of life to be found in all Gerwig’s films is intermixed with the troubles that affect an imperfect world. As a creative minded person, one moment that I remembered most vividly from other adaptations of Little Women is when Amy burns Jo’s manuscript as a petty act of revenge. Gerwig introduces this flashback right after Jo returns home to help care for Beth during her second illness. When Marmee and Meg mention that Beth requested they not tell Amy so she wouldn’t cut her time in Paris short, Jo retorts, “Amy has always had a talent for getting out of the hard parts of life.” And Marmee responds, “Don’t be angry at your sister.”

At that point, the film flashes back to the infamous episode where Jo tells Amy she’s not welcome to accompany her and Meg on a double date, and Amy burns her novel out of revenge. Gerwig’s choice not to double cast the film and have the same actresses play the adult sisters and the young girls as they recollect their shared childhood strengthens the memory element throughout the film, and it highlights the bond that cannot be broken even when it is damaged. It also enabled Florence Pugh to give a phenomenal performance playing both twenty and thirteen with equal aplomb. Finally, it establishes Amy as a co-protagonist with Jo, showing that Jo’s comment about Amy avoiding life’s hard parts is untrue.

Jo’s understandable rage at discovering her manuscript destroyed gives way to a line often omitted in adaptations of Little Women. As Marmee consoles a self-flagellating Jo for almost allowing her little sister to drown, she tells Jo she suffers from excessive anger as well. “I’m angry nearly every day,” Marmee tells her daughter, but she’s learned how to manage it, adding that her daughter will learn to do so a great deal better than she has. And the film proves her right, as Jo says toward the end, “Life is too short to be angry at one’s sisters.”

For all the joy and love in Gerwig’s three films thus far, anger and grief are two emotions that depicted just as much. Honestly, I think Gerwig’s choice to depict the intensity of her character’s emotions along with people hurt by them is what makes the moments of joy, grace, and love all the more powerful. Watching Little Women five times in theaters, I could never pinpoint why Beth’s death hit so hard every time. However, rewatching it post-Barbie gave me an insight that holding the happy-sad moments together is what makes both of them felt so much more strongly.

Rhea Perlman’s final line to Barbie as Ruth Handler is: “Feel.” Those feelings are throughout Barbie and Little Women. And it is that feeling which enables Barbie to become human. All three of Gerwig’s films end with a transformation. Lady Bird becomes Christine; Jo March becomes a published author; and Barbie becomes a woman. And all three of these transformations show an extension of grace and celebration of life in its full complexity.

However, in Gerwig’s films, grace is not only extended to the protagonists. It is extended to every character whether they deserve it or not. I’ve seen critics of Barbie and Lady Bird call them angry movies, and nothing could be further from the truth. They’ve overflowing with love, not just for their protagonists, but for everyone else in their casts as well. This love is a recognition that everyone can be better, and it is a call for the protagonists and viewers to be better as well.

One such example is the exchange between Lady Bird and her mother when they’re dress shopping for the senior prom. After a mild criticism from her mother, Lady Bird asks, “Do you like me?” Her mom sighs and says, “Of course I love you.” To which Lady Bird says, “Yeah, but do you like me?” Her mom: “I want you to be the very best version of yourself that you can be.” Lady Bird: “What if this is the best version?”

Even within this far from perfect exchange between mother and daughter, several important points are made. Love does call us to be the best version of ourselves, but it also calls us to accept people as they are. You cannot love an idea of a person; that’s infatuation. The reality that many family members love each other without particularly liking each other is a regrettable fact. It’s a flawed love without doubt, but that love can grow and improve, and Lady Bird gives a phenomenal example of such growth in its heart-wrenching final monologue.

In Barbie, a lesser filmmaker would have made Ryan Gosling’s Ken or Will Ferrell’s Mattel CEO oppressive threats to be destroyed rather than victims of patriarchy to be pitied. Ferrell receives a moment of grace when he reprimands an executive not worried about Mattel’s products as long as they sell, even as he clearly is blinded by how much a patriarchal system has benefitted him. One of the most uncomfortable scenes in Barbie is when Stereotypical Barbie apologizes to Ken for leading him on and tells him he needs to find an identity that is not his girlfriend, not his occupation, and not even beach. Given the ways Ken wrecked Barbieland by bringing back patriarchy and oppressing the Barbies, spitting in his face may seem like the more natural response. However, remember that in Barbieland’s inverse patriarchy, Ken inhabited a world where he was made for Barbie’s pleasure and companionship and throughout most of their lives, she did hold the power in the relationship, because Barbie is Mattel’s signature toy, not Ken. That apology may seem undeserved, but as the film portrays Ken as a victim of patriarchy, it is fitting that grace extends to a toy who needs to undergo his own healing path.

There have never really been villains in any screen adaptation of Little Women, although some of them make Aunt Josephine colder and harsher than others. At this point, it should not be a surprise that Gerwig does not go that route in her envisioning of the character, and Meryl Streep’s portrayal of her is stern but clearly concerned about her nieces. She does not object too strongly to Amy and Laurie’s romance; she leaves Jo her house to start a school, and she takes in Amy when Beth falls ill the first time.

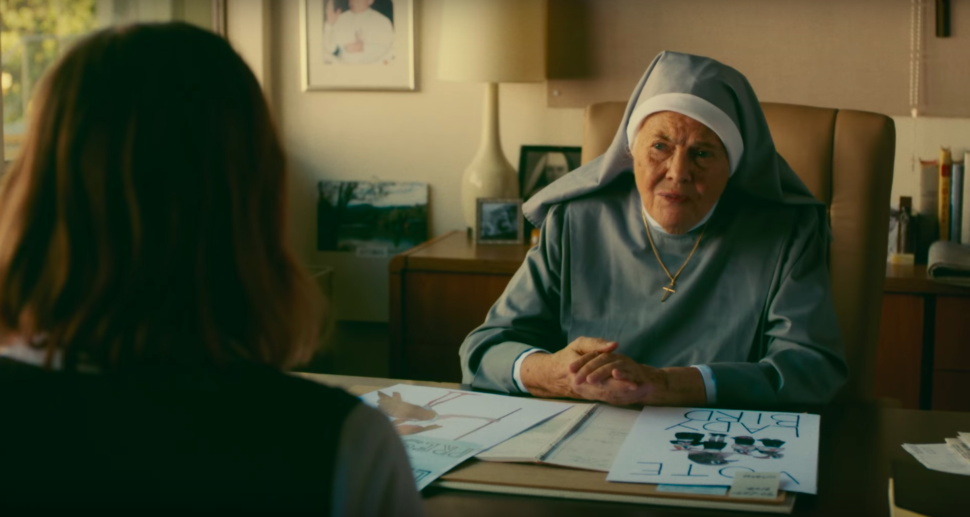

As a concluding, and possibly most important, point, Gerwig’s film showcase love through paying attention. In an oft referenced scene from Lady Bird, when the title character meets with her school principal, Sister Sarah Joan (Lois Smith), to discuss her college essay the nun comments how much Lady Bird clearly loves Sacramento. Taken aback, Lady Bird asks why she said that. The nun responds it’s the affectionate and careful description she gives her home city. Lady Bird says, “Sure, I guess I pay attention.” And then Sister Sarah Joan delivers this bit of wisdom: “Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing: love and attention?”

If showing attention is love, then I can think of no living filmmaker with more love for her characters, her audience, and the world than Greta Gerwig. Barbie’s line about paying attention to the real world and all its troubles made her not wish to remain a doll. It was that connection to Lady Bird that inspired this essay for me. The love Barbie felt after encountering a world outside her perfect bubble is what spurred her final transformation. And that’s not dissimilar from a love for her parents that spurs Christine’s final phone call in Lady Bird.

Examples of love through attention abound in Gerwig’s three films. When the March sisters give away their Christmas breakfast to a starving family, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) notices them and has his grandfather arrange another feast for them. When Laurie’s grandfather notices Beth’s shy disposition, he quietly drops he’d love it if someone would come over and play his daughter’s piano. When Larry McPherson (Tracy Letts) notices his son going for the same job he applied for, he straightens his tie and wishes him luck. When Father Leviatch notices Julie’s heartfelt, if slightly off-pitch, rendition of “Make Me a Channel of Your Peace” he casts her as the musical lead. When Gloria (America Ferrera) starts missing her little girl who’s turned into an angsty tween, Gloria’s love of their old games manifests through unusually detailed drawings.

When those drawings cause a rift in the portal between Barbieland and the real world, the differences between fiction and reality become messy. But it is that messiness which reveals so much not just about the Barbies, but Gloria and her daughter as well. The joy Jo feels at the end of Little Women would not have happened had she been the one to go to Europe instead of Amy. As Gerwig blurs the fiction and autobiographical nature of Alcott’s novel, we see how art and life reflect one another. In Lady Bird, the dreams of a flamboyant teenager to escape her hometown and go to the East Coast to experience culture only reveal how powerful the bonds of one’s home and upbringing are. All of these messy contradictions are a reality of life, and that is what Gerwig captures so beautifully. Her films are living, breathing works that invite an ongoing relationship with each one of them. As Gerwig said in her character of Frances over a decade ago: “And it’s funny and sad, but only because this life will end, and it’s this secret world that exists right there in public, unnoticed, that no one else knows about. It’s sort of like how they say that other dimensions exist all around us, but we don’t have the ability to perceive them. That’s—that’s what I want out of a relationship. Or just life, I guess.” That’s what my favorite movies depict, and why I can’t wait to see how Gerwig’s career unfolds.

Oklahoma!

Posted by Evan in Uncategorized on August 20, 2016

A big thanks to Ken Morefield for inviting me to contribute to his series on Fred Zinnemann with this retrospective on Oklahoma!

Cinderella and Cinematic Saints

Posted by Evan in Uncategorized on April 18, 2015

Disney’s recent live action film of Cinderella provides what has become — perhaps fortunately, perhaps unfortunately — a unique take on the fairytale. It is a straightforward, old-fashioned telling of the traditional story without any deconstruction, subversive twists, or rewriting of roles, all of which have become increasingly common in recent tellings of fairy stories from Wicked to Shrek to Frozen to Maleficent. (That statement is meant neither as a criticism nor as compliment, just a mere fact.)

In adapting Cinderella, director Kenneth Branagh said that he wanted to make a movie which showed kindness to be a superpower. That approach enabled him to preserve the classical elements of the fairytale and create a heroine who is intelligent and resourceful while refusing to become bitter and vindictive due to the misfortunes she suffers.

Aren Bergstrom of Three Brothers Film made an insightful comparison regarding Cinderella‘s “kindness as a superpower” theme on Twitter. Aren suggested that Branagh’s take on the classic fairytale heroine puts her in a similar league with cinematic saints like Thomas More in A Man For All Seasons and Joan in The Passion of Joan of Arc, a comparison which is not undeserved.

One recurring line in Cinderella is what Ella’s mother (Hayley Atwell) says to her daughter (Lily James) before she dies: “Be kind and have courage.” That line could also be applied to some of the most determined and most inspiring cinematic portrayals of saints from the past century.

In 1928 Carl Theodor Dreyer’s silent masterpiece, The Passion of Joan of Arc, gave audiences what is possibly the ultimate cinematic example of a suffering servant. Comprised primarily of long takes and still close-ups, Dreyer’s film dwells on the sufferings of Joan through her trial and martyrdom, and with evocations of Biblical imagery, such as a crown of thorns and a lamb led to the slaughter, the film clearly suggests that Joan’s sufferings are a way for her to partake in the passion, death, and resurrection of Christ.

Throughout her tribulations, Joan of Arc, much like Branagh’s Cinderella, never becomes bitter or angry toward her persecutors. Sorrowful and fearful, yes, but both of them face their sufferings which dignity and all the courage they can muster (which must be pointed out, is far harder for Joan as she is being tortured and threatened with death). After their worst trials, both of them receive a gift of grace which brings them to a new and better home, something which is also true for the following examples.

Finally, I am sure this is a coincidence, but even if this pose is a common villain expression, the similarity between these shots of Cate Blanchett as Lady Tremaine and Eugene Silvain as Bishop Pierre Cauchon (Joan of Arc’s chief persecutor) is worth pointing out.

Another cinematic saint who has even more in common with Branagh’s Cinderella is Bernadette Soubirous as played by Jennifer Jones in The Song of Bernadette (1943). Bernadette may have come from a loving and supportive family, but her frail health caused her much pain throughout her life, pain which she always bore courageously as she treated everyone with love and kindness, even when she least wished to. On top of that, her visions of the Blessed Mother asking for a chapel to be built were received with skepticism by a couple of the religious authorities and outright disdain and threats by the town magistrates. The Song of Bernadette suggests that one reason the magistrates bully and threaten a young, defenseless girl is that in secular and agnostic post-revolution France, the officials did not care to see a mass-hysteria over what they viewed to be an antiquated belief system.

To my knowledge, there has been no backlash against Cinderella, but like Bernadette called attention to something which many thought of as passé, Cinderella portrays a world and style of storytelling steeped in classicism that noticeably contrasts our increasingly cynical postmodern culture.

If Robert Bolt’s brilliant screenplay for the 1966 A Man for All Seasons does not constitute one of the most inspiringly quotable movies ever, then I don’t know what would. Cinderella‘s screenplay by Chris Weitz is not on the same level as that of A Man for All Seasons, but there is one line that captures Cinderella’s bravery and compassion, which she shows to everyone, even her step-family, even after they have been unusually cruel toward her. That line is, “They treat me as well as they’re able,” and it expresses a similar sentiment to the final words spoken by Thomas More after he has been found guilty of treason via an obvious perjury.

I am the King’s true subject, and pray for him and all the realm. I do none harm, I say none harm, I think none harm. And if this be not enough to keep a man alive, in good faith I long not to live. I have, since I came into prison, been several times in such a case that I thought to die within the hour, and I think Our Lord I was never sorry for it, but rather sorry when it passed. And therefore, my poor body is at the King’s pleasure. Would God my death might do him some good.

Sophie Scholl may not be a canonized saint of the Catholic Church, but there can be little doubt that she is in heaven. As an active member of the White Rose, an underground resistance group to the Nazis, she was executed along with her brother Hans for treason against the Third Reich. Their arrest and trial are dramatized in the 2005 film Sophie Scholl: The Final Days. The film primarily focuses on Sophie, and the young protagonist is another example of a heroine who remains dignified and courageously kind in the face of adversity which can often seem inhuman.

One of the most noticeable similarities between Cinderella and Sophie is that both of them choose not to hold a grudge against those who cause their suffering. Indeed, Sophie’s calmness as she is interrogated takes an admirable level of self-control, much like Cinderella’s final action in Branagh’s film. Even when they are imprisoned unjustly, both women care for others who are worse off than they. Finally, both also have the humility to realize when they need help and spiritual guidance from someone else and accept it.

Although the film is a fairytale rather than a dramatization of an historical event, Cinderella features a protagonist with similar traits to some of the most dignified and determined saints who have graced the silver screen. However, it is fitting that a fairytale should continue this characterization. As I’ve said before, at a fundamental level, fairytales are morality tales for children. In opting for a classical retelling of Cinderella, with its saintly protagonist, Branagh’s film lauds two virtues which are found in some of the most famous cinematic portrayals of saints, two virtues which do have a sort of superpower to carry one through suffering to a new and better world: courage and kindness.