Batman Returns

Year of release: 1992. Directed by Tim Burton. Starring Michael Keaton, Michelle Pfeiffer, Danny DeVito, and Christopher Walken.

The first (brief) review I wrote of Batman Returns began as follows: “Everything about this film can be explained by simply remembering this is not Batman film, it is not a superhero film, it is a Tim Burton film. And it is a Tim Burton film about three psychopaths with parent issues who costume play while endangering the lives of every resident in Gotham City.”

If you’re wondering who the three psychopaths are, they are Danny DeVito’s Penguin, Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman, and Michael Keaton’s Batman. I believe Batman murders four people in this film—two of whom he kills upon his first screen entrance. DeVito’s grunting, grotesque, and strangely sex-starved Penguin with his bizarre revenge plot is the obvious villain, and while Pfeiffer’s sinister Catwoman is a far cry from the sympathetic Selina Kyle of later screen adaptations, her unresolved parent issues and ticking maternal clock make for a perfectly explosive femme fatale to foil both the Penguin and Batman.

While the Penguin is the obvious villain, Christopher Walken’s business mogul Max Shreck rivals him for control of Gotham City in a game of politics where they continually shift between allies and enemies. Have I mentioned that Keaton’s emotionally repressed Batman and Bruce Wayne is barely in this film? It’s vastly superior to Burton’s 1989 Batman for that alone, and the little we see of this stoic caped crusader only serves to reinforce that he’s as unhinged as his two nemeses.

I, and others, have included Batman Returns on the list of great Christmas movies, because it is set completely around Christmas. For a holiday about the Incarnation, reconciliation between heaven and earth, and a time of general peace and good will on earth, a movie about sexually repressed psychopaths with traumatic childhoods taking out their anger and neuroses on an entire city populace as they all navigate a late-stage capitalist hellscape controlled by one equally corrupt, but boringly idiotic, man simply because he has money, may not seem like a normal choice for festive cheer. However, if there ever were an in absentia depiction of a world that needed a savior, this is it.

A later and more beloved film about the Dark Knight calls him the hero we deserve, not the one we need. In Batman Returns, it’s a stretch even to call him a hero. There is a case to be made that Catwoman is the actual hero here given she sacrifices one of her nine literal lives to murder Shreck, and as the character who bears the brunt of capitalism’s oppression, her insanity has the most natural causes behind it. For the record, I would not make that case—this film has no heroes in my book—but while this incarnation of Catwoman is more evil than later ones, it is possible to say she’s more righteous and realistic than any other character.

Pfeiffer delivers the lines of a repressed and rebellious femme fatale with such camp and passion that the psychopathy of all the major characters comes into focus around her. The contrast of her two entrances into her pink, one bedroom apartment so perfectly captures the transformation of a bachelorette longing for partnership with a burned-out bitch determined to screw over those who have made her life hell, which is noted through the changing set design of her bedroom.

Catwoman’s shifting hatred between Shreck and Batman, may seem unreasonable, but as a psychopath, why should she be expected to think reasonably? As she says, “Life’s a bitch, and so am I,” and she sees to it to dish that bitchiness out to anyone who gets in her way. Also, as both Schreck and Batman are two filthy rich capitalists, they are more similar than not. Thankfully, Batman Returns does not have the handwringing over billionaires using their wealth to save a city as Robert Pattinson’s Batman did. Nor does it entertain any questions about Batman being a hero or a villain as Nolan’s trilogy did, despite Keaton’s Batman being one of the most unethical screen versions of the superhero. It takes the comic book conventions at face value and runs with them, along with running with its own bonkers premise—including, but not limited to, the scene where Pfeiffer self-grooms her leather catsuit and deepthroats a parakeet to intimidate the Penguin.

In the age of the MCU and a general cinematic obsession with realism, I cannot begin to describe how refreshing this straightforward, pulpy camp is to watch. From the practically un-choreographed fight sequences to villains randomly pointing guns in the air to everyone pausing to watch the acrobatics of whom they’re fighting, the lack of realism makes this fantasy world a delight. I’m still not sure I’d call this Burton’s best film, although it is unquestionably a contender, but it is without a doubt the most Tim Burton film ever.

There’s something tragically appropriate about a Christmas film calling a corrupt capitalist the Santa Claus of a city, which is how Shreck is introduced. While Santa is a myth with a tangential relationship to the true meaning of Christmas, there is a rite of passage for many children when they learn the truth about Santa and Christmas presents. In Batman Returns, the orphaned Batman, the rejected Penguin, and the estranged Catwoman were all clearly deprived of healthy, formative relationships with their parents, and letting those family tensions erupt over Christmastime at the cost of an entire society is a delightfully campy masterstroke.

Even more fittingly, in a world that needs a savior, or has lost any spirit of Christmas, mistaking capitalist greed for generosity, which the citizens of Gotham do as they lionize Shreck, makes this tragic hellscape all the more quintessentially Burtonesque. The Gotham police’s reliance on Batman is yet another wish for more money to save the day. The commitment to this campy tragedy escalates perfectly until the only way to wake up from the nightmare is to see mommy kissing Santa Claus. And at that point, as innocence is shattered, no amount of presents or money can solve childhood trauma or capitalism’s injustice. So that’s when you get a cat. Merry Christmas.

Personal recommendation: A+

Life’s Messy Discomfort through the Lens of Greta Gerwig

Spoilers should be assumed for Lady Bird, Little Women, and Barbie.

I remember watching Frances Ha in the summer of 2012 and being instantly swept away by the heartfelt realism, painfully relatable comedy, and pervading sense of optimism throughout the film. It quickly became my favorite Noah Baumbach film, and I half-jokingly, half-seriously said I had either lived every scene in it or knew someone who had. While Frances Ha may not have been my first introduction to Greta Gerwig, it certainly was the first time I was aware of her as an artist as she danced through the streets of New York in glorious black and white.

Now just over a decade later, Gerwig has written several more screenplays and directed three movies of her own. Anyone who has followed any portion of my film commentary over the last five years knows that I adore Lady Bird like few other movies and possibly that I saw her Little Women five times in theaters. And Barbie has only grown tremendously in my estimation after two viewings.

With the exception of Wes Anderson, I cannot think of any auteur working today other than Gerwig who makes movies that depict an imperfect world with so much joy, hope, and love. From Lady Bird to Barbie, Gerwig has captured a recognition of the potential the world has to be good with a full awareness of how it should be in the midst of all of its shortcomings. This notion comes from Graham Greene and his writings on film criticism, and when movies can capture that sort of expression, they show an act of creation partaking in the glory of all creation. Indeed, given the Genesis-inspired themes in Barbie, it is easy to imagine Gerwig as a creator looking over her films and their views of the world and pronouncing them both good.

The goodness of the worlds depicted in Gerwig’s films shows an incredible sense of hope given the heartaches, betrayals, and ways characters can hurt one another and themselves. In a review of Frances Ha published a decade ago, Eve Tushnet wrote: “Frances herself is just a beautiful character. You get how she can be exasperating. She’s impulsive, she lets her dreams consume and threaten her real life, she’s awkward in a way which can come across as self-centered and idealistic in a way which can come across as entitled. She’s too much, consistently. But she’s also just a joy to be around.” I think it is very much worth pointing out that Frances is played by Gerwig and clearly a character created out of love and that Eve titled her review “Hope Stumbles Eternal.”

As a concise summary of what I love about all of Gerwig’s movies, I think “Hope stumbles eternal” could be applied from Lady Bird to Little Women to Barbie. Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson, Jo March, and Stereotypical Barbie are three very different protagonists, but from falling out of a car to having trips to Europe taken away to getting flat feet, all of them take literal and figurative falls that open new paths to discover that aforementioned hope along with joy and love.

The first time I saw Lady Bird, the scene that delighted me the most was the musical audition where all the high school kids sang Sondheim, except for Beanie Feldstein’s Julie. It was such a delightful surprise to see and hear that many Sondheim songs as high school performers bit off more than they could chew, and it was a microcosmic way of showing the dreams and aspirations for what the world can be and the less than perfect reality. Barbie contains a similarly delightful surprise with its prologue homage to 2001: A Space Odyssey. In the simplified and erroneous view of the Barbies, the invention of Barbie, like the obelisk in 2001, spurred humankind, specifically women, to take tremendous steps forward in progress and equality. It expresses the hopeful desires of feminism while eliciting laughs for the far the less-than-ideal reality that every viewer is aware of.

Continuing with the 2001 homage, the finale of Barbie frames the film with several Kubrick references. The dialogue between Barbie and her creator, Ruth Handler (Rhea Perlman), takes place in a white void, not dissimilar to the room at the end of 2001. In both films the protagonist is then reborn. In Barbie, right before this rebirth Barbie says that life has gotten too complicated and discomforting to go back to Barbieland. And yet, Gerwig—through Perlman’s urging Barbie to feel and through the montage of the joys and pains of life—says this discomfort and messiness is nothing to be afraid of, but something to be embraced. The final zinger that Robbie delivers after that scene is unquestionably reminiscent of the final lines in both A Clockwork Orange and Eyes Wide Shut.

How do two dystopian nightmares such as those Kubrick films (one comedy, one horror) tie into a depiction of the world as it is and as it should be? Wouldn’t those two films more accurately depict worlds that no one would want to inhabit? While the answer to that second question is yes for any non-psychopath, both Kubrick films exaggerate the dysfunction of a world where freewill is eradicated (through over-the-top comedy) and the danger of a world where fidelity is tossed aside (through creepy sexual rituals). In both cases, there is a clear acknowledgement of what is broken with a realization of how things should be different.

Barbieland itself is a brilliant inversion of patriarchy. As a means of highlighting the dysfunctional and sexist nature of a patriarchal society, showing a world where the Kens are subjugated, hold no positions of power, and exist only for the Barbies’ entertainment and companionship reveals the objectification many women have experienced in the real world, while simultaneously laughing in the face of patriarchy. Indeed, the absurd accusations of misandry from the film’s critics make it clear that the parody hit its intended mark.

For all that has been made of America Ferrera’s dramatic third act speech in Barbie, I’m surprised that almost no one (or literally no one?) has pointed out that Saoirse Ronan makes nearly the same speech toward the end of Little Women. Both speeches could be considered a sort of condensed feminist manifesto. Ferrera’s exasperated mother and Barbie lover Gloria voices the disconnect and absurd double standard of being a woman under patriarchy—thus robbing the patriarchy of its power by giving voice to that cognitive dissonance, which Robbie’s Stereotypical Barbie points out to her own shock.

Near the end of Little Women, after Jo has watched one of her sisters die, lost a trip to Europe she dreamed of, rejected an offer of marriage, and had her short stories severely critiqued by a friend, she is reconsidering what to make of her life. In a similarly dramatic speech to the one in Barbie, she exclaims to Marmee: “Women, they have minds, and they have souls, as well as just hearts. And they’ve got ambition, and they’ve got talent, as well as just beauty. I’m so sick of people saying that love is just all a woman is fit for. I’m so sick of it.” Then after a beat she adds much more somberly, “But I’m so lonely.”

That following line voices the same dissonance as Ferrera’s big speech in Barbie and the less-than-ideal reality that many people often experience in life. It in no way undermines Jo’s desire for independence and dreams of being a self-sustaining writer. Jo’s happiness in a marriage only comes after she is fully happy as herself. When she agrees to end her novel with a marriage so it will sell, she quotes Amy’s earlier line that “marriage has always been an economic proposition.”

At the same time, Little Women shows loving, healthy marriages. All of them have struggles and quarrels, but the beauty of the relationships and love between the couples cannot be overlooked. As Jo suggests to Meg on her wedding day that the two of them run away and support themselves through writing and acting, Emma Watson’s response reminds Jo and the viewer of the validity of all vocations. “Just because my dreams are different than yours doesn’t mean they’re unimportant.”

Recognizing the importance of marriage and independence ultimately gives the portrayal of relationships in Little Women more depth and affection. The ability to hold two ideas as equals that society often says need to be opposites is a sign of the beauty to be found in life’s discomforting moments—both moments of joy and loneliness. Put another way, as Lawyer Barbie says, “This makes me emotional and I’m expressing it. I have no difficulty holding both logic and emotion at the same time, and it does not diminish my powers. It expands them.”

Simultaneously holding logic and emotion is not something that Ronan’s headstrong teenage Lady Bird does. Nor does her equally strong-willed mother played by Laurie Metcalf. The tempestuous relationship between mother and daughter forms most of the conflict in Lady Bird, punctuated by the ups and downs of a senior year of high school.

That central conflict along with the supporting ones is captured by the film’s prologue. Lady Bird and her mother finish college visits and complete the audio book of The Grapes of Wrath as they drive home, and the initial moment of bonding quickly turns sour as the Lady Bird’s dreams of attending an East Coast college, experiencing culture, and becoming famous jar with her mother’s practical sense of reality. Both actresses deliver Gerwig’s sharp retorts with such humor that the toxicity of the relationship could be overlooked in this scene. When Lady Bird rolls out of the moving car and breaks her arm, it should be more apparent, especially when the next cut is to a closeup of her cast with “Fuck you, Mom” written on it in tiny print.

I think the tension created from that opening sequence—which builds throughout the film via secret college applications, careless slips from boyfriends, school suspensions, and more—is one reason the ending of Lady Bird is so powerful. (Since my first viewing of Lady Bird, I have cried all fifteen or so additional times that I’ve seen it at the ending.) First and foremost, the ending of Lady Bird expresses a desire and hope for healing from abusive relationships. Secondly, it taps beautifully into the messy imperfections of the world as it is and realizes there is a better way for it to be.

It is very important to mention that Lady Bird does not absolve Laurie Metcalf’s emotionally abusive mother. Metcalf is so fantastic in the role that it becomes easy to sympathize with her character as we see an overworked mom trying the best to provide for her family and afraid of losing them. The possibility of reconciliation is brought about by mediation through Tracy Letts’ father (in an equally amazing performance). After Lady Bird receives the handwritten letters, she reaches out in response to them. (If you haven’t paused Lady Bird while watching it to read those letters, you need to do so.)

The final phone call in Lady Bird, complete with crosscuts between Metcalf and Ronan driving the same Sacramento streets, is unquestionably the greatest scene Gerwig has shot thus far. The comparison between mother and daughter, acknowledgment of the dysfunctional relationship, and depiction of the love that both of them have for each other is perfectly portrayed. It is not a moment of reconciliation, as the phone call is a voicemail and we never see where the relationship goes moving forward, but it is a first step of healing as Christine realizes that there are indissoluble bonds with her parents.

For many people who have toxic relationships with their parents, and especially for those who have gone no contact, such a scene may be very difficult to watch. I won’t deny a large part of the emotions I feel during the finale of Lady Bird stems from my own strained family relationships. However, returning to the Graham Greene quote at the beginning of this essay, Lady Bird depicts a healing that everyone should wish for regardless of whether or not it is attainable in this world. For me, the longing for that healing makes the scene just as cathartic if not more so than had that healing occurred, because the longing is what creates the happy-sad tension between what is and what should be.

As Christine walks off her first hangover after moving to New York for college, stumbling into a church reminds her of her parents and need for connection. I vividly remember my first hangover and the guilt I felt afterwards, and reaching out for a nurturing connection is a natural response. Had it not been for the letters that Christine found in her college suitcase, she would have left home without any of that nurture, and her final phone call would have come across as undeserved forgiveness for her mom. (Again, pause your Blu-ray/stream of Lady Bird and read those letters.) It is at the lowest moment of messy brokenness that Lady Bird (and all of us) turn outward to realize our interconnectedness.

As the montage that Stereotypically Barbie watches before she becomes human also shows, that interconnectedness is inherently messy, and that is a beautiful thing. Barbie also has a quintessential moment of brokenness and dejection, not dissimilar to Lady Bird’s hangover; however, that moment is responded to with an hilarious joke from Helen Mirren’s narrator.

It is a truth universally acknowledged, “that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife,” to quote Jane Austen and hat-tip another Barbie reference, and that tragedy and comedy are two sides of the same coin. Barbie’s comedic response to its protagonist hitting rock bottom is not that dissimilar from heartfelt phone call that ends Lady Bird. As Stereotypical Barbie cries that she failed the Barbies and that she has turned ugly and ordinary, Mirren states: “Note to the filmmakers: Margot Robbie is the wrong person to cast if you want to make this point.”

The difference in how we perceive ourselves after any literal or figurative fall and the reality of our inherent worth is often at odds. Mirren’s narration humorously rips an old-fashioned societal notion that everything has to go perfectly and women have to look their best to be beautiful. It builds on the earlier scene when Barbie tells an older woman who does not fit patriarchal standards of beauty that she is beautiful, and she replies, “I know it.” That self-confidence is something we should all aspire to, and given Barbie’s ending about embracing life as we are, it does not seem a stretch to say that old woman is an example of a life well lived. (Given that the woman is framed next to a recycling bin, I think there’s an obvious connection between the different stages of observing the overlooked woman recycling a bottle throughout Kieslowski’s Three Colors Trilogy, but that may be coincidental.)

Returning to the similarity with the ending of Lady Bird, when Christine calls her parents, she is reaching out for a connection after a bad fall and accepting herself and her mom with both of their imperfections. Living into her truth as herself, it is the first time in the film that Christine uses her name and not her moniker of teen rebellion that she went by for most of the film. Like Mirren’s joke in Barbie, Ronan’s entire monologue is a statement that she and her mom are beautiful people despite the tumbles they’ve both taken. Continuing the Kieslowski similarities, the way Irene Jacob lays her hand on the tree that connects her and her double at the end of The Double Life of Veronique could be another coincidental point of comparison.

Given that Lady Bird opens with another fall, framing this story of grace with two falls—one literally out of a car and the second an emotional fall after rushing to the emergency room in a panic over first time intoxication—reflects how strongly hope stumbles eternal in the cinema of Greta Gerwig. Barbie’s transition into a real girl in acknowledgement of the imperfections of both Barbieland and the real world is an embracing of such falls. And the emotional growth of all the March sisters in Little Women is almost always juxtaposed with such falls.

In reordering the chronology of Alcott’s novel, Gerwig highlighted different aspects of the well-known story through juxtaposing specific later events with earlier ones. What Gerwig also achieved through this editing was turning the main plot of the story into a young struggling writer returning home to face the death of her younger sister, while remembering the good and bad memories they had with their family. These memories end up forming the titular novel, and as the opening quote from Alcott states: “I’ve had lots of troubles, so I write jolly tales.”

Little Women is at its heart a jolly tale of love between sisters. That does not mean it does not contain its share of troubles, since the joy of life to be found in all Gerwig’s films is intermixed with the troubles that affect an imperfect world. As a creative minded person, one moment that I remembered most vividly from other adaptations of Little Women is when Amy burns Jo’s manuscript as a petty act of revenge. Gerwig introduces this flashback right after Jo returns home to help care for Beth during her second illness. When Marmee and Meg mention that Beth requested they not tell Amy so she wouldn’t cut her time in Paris short, Jo retorts, “Amy has always had a talent for getting out of the hard parts of life.” And Marmee responds, “Don’t be angry at your sister.”

At that point, the film flashes back to the infamous episode where Jo tells Amy she’s not welcome to accompany her and Meg on a double date, and Amy burns her novel out of revenge. Gerwig’s choice not to double cast the film and have the same actresses play the adult sisters and the young girls as they recollect their shared childhood strengthens the memory element throughout the film, and it highlights the bond that cannot be broken even when it is damaged. It also enabled Florence Pugh to give a phenomenal performance playing both twenty and thirteen with equal aplomb. Finally, it establishes Amy as a co-protagonist with Jo, showing that Jo’s comment about Amy avoiding life’s hard parts is untrue.

Jo’s understandable rage at discovering her manuscript destroyed gives way to a line often omitted in adaptations of Little Women. As Marmee consoles a self-flagellating Jo for almost allowing her little sister to drown, she tells Jo she suffers from excessive anger as well. “I’m angry nearly every day,” Marmee tells her daughter, but she’s learned how to manage it, adding that her daughter will learn to do so a great deal better than she has. And the film proves her right, as Jo says toward the end, “Life is too short to be angry at one’s sisters.”

For all the joy and love in Gerwig’s three films thus far, anger and grief are two emotions that depicted just as much. Honestly, I think Gerwig’s choice to depict the intensity of her character’s emotions along with people hurt by them is what makes the moments of joy, grace, and love all the more powerful. Watching Little Women five times in theaters, I could never pinpoint why Beth’s death hit so hard every time. However, rewatching it post-Barbie gave me an insight that holding the happy-sad moments together is what makes both of them felt so much more strongly.

Rhea Perlman’s final line to Barbie as Ruth Handler is: “Feel.” Those feelings are throughout Barbie and Little Women. And it is that feeling which enables Barbie to become human. All three of Gerwig’s films end with a transformation. Lady Bird becomes Christine; Jo March becomes a published author; and Barbie becomes a woman. And all three of these transformations show an extension of grace and celebration of life in its full complexity.

However, in Gerwig’s films, grace is not only extended to the protagonists. It is extended to every character whether they deserve it or not. I’ve seen critics of Barbie and Lady Bird call them angry movies, and nothing could be further from the truth. They’ve overflowing with love, not just for their protagonists, but for everyone else in their casts as well. This love is a recognition that everyone can be better, and it is a call for the protagonists and viewers to be better as well.

One such example is the exchange between Lady Bird and her mother when they’re dress shopping for the senior prom. After a mild criticism from her mother, Lady Bird asks, “Do you like me?” Her mom sighs and says, “Of course I love you.” To which Lady Bird says, “Yeah, but do you like me?” Her mom: “I want you to be the very best version of yourself that you can be.” Lady Bird: “What if this is the best version?”

Even within this far from perfect exchange between mother and daughter, several important points are made. Love does call us to be the best version of ourselves, but it also calls us to accept people as they are. You cannot love an idea of a person; that’s infatuation. The reality that many family members love each other without particularly liking each other is a regrettable fact. It’s a flawed love without doubt, but that love can grow and improve, and Lady Bird gives a phenomenal example of such growth in its heart-wrenching final monologue.

In Barbie, a lesser filmmaker would have made Ryan Gosling’s Ken or Will Ferrell’s Mattel CEO oppressive threats to be destroyed rather than victims of patriarchy to be pitied. Ferrell receives a moment of grace when he reprimands an executive not worried about Mattel’s products as long as they sell, even as he clearly is blinded by how much a patriarchal system has benefitted him. One of the most uncomfortable scenes in Barbie is when Stereotypical Barbie apologizes to Ken for leading him on and tells him he needs to find an identity that is not his girlfriend, not his occupation, and not even beach. Given the ways Ken wrecked Barbieland by bringing back patriarchy and oppressing the Barbies, spitting in his face may seem like the more natural response. However, remember that in Barbieland’s inverse patriarchy, Ken inhabited a world where he was made for Barbie’s pleasure and companionship and throughout most of their lives, she did hold the power in the relationship, because Barbie is Mattel’s signature toy, not Ken. That apology may seem undeserved, but as the film portrays Ken as a victim of patriarchy, it is fitting that grace extends to a toy who needs to undergo his own healing path.

There have never really been villains in any screen adaptation of Little Women, although some of them make Aunt Josephine colder and harsher than others. At this point, it should not be a surprise that Gerwig does not go that route in her envisioning of the character, and Meryl Streep’s portrayal of her is stern but clearly concerned about her nieces. She does not object too strongly to Amy and Laurie’s romance; she leaves Jo her house to start a school, and she takes in Amy when Beth falls ill the first time.

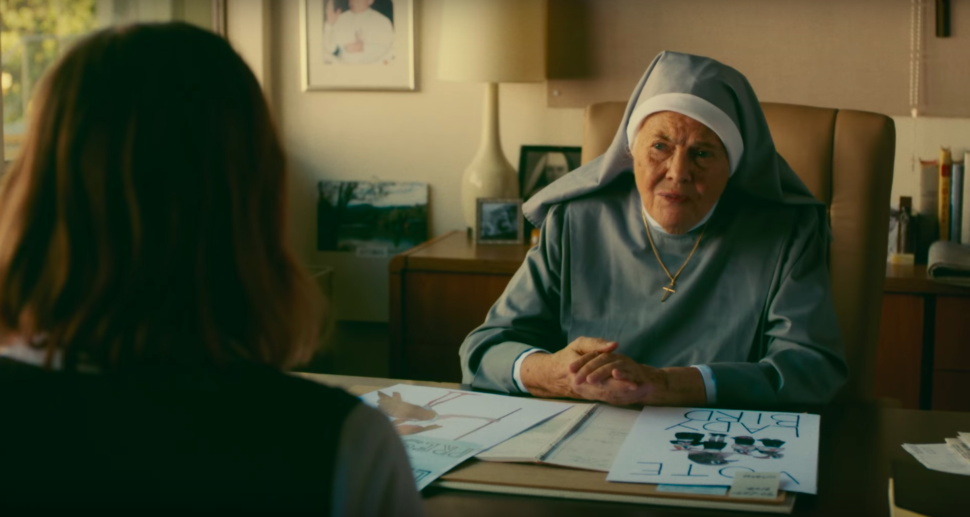

As a concluding, and possibly most important, point, Gerwig’s film showcase love through paying attention. In an oft referenced scene from Lady Bird, when the title character meets with her school principal, Sister Sarah Joan (Lois Smith), to discuss her college essay the nun comments how much Lady Bird clearly loves Sacramento. Taken aback, Lady Bird asks why she said that. The nun responds it’s the affectionate and careful description she gives her home city. Lady Bird says, “Sure, I guess I pay attention.” And then Sister Sarah Joan delivers this bit of wisdom: “Don’t you think maybe they are the same thing: love and attention?”

If showing attention is love, then I can think of no living filmmaker with more love for her characters, her audience, and the world than Greta Gerwig. Barbie’s line about paying attention to the real world and all its troubles made her not wish to remain a doll. It was that connection to Lady Bird that inspired this essay for me. The love Barbie felt after encountering a world outside her perfect bubble is what spurred her final transformation. And that’s not dissimilar from a love for her parents that spurs Christine’s final phone call in Lady Bird.

Examples of love through attention abound in Gerwig’s three films. When the March sisters give away their Christmas breakfast to a starving family, Laurie (Timothée Chalamet) notices them and has his grandfather arrange another feast for them. When Laurie’s grandfather notices Beth’s shy disposition, he quietly drops he’d love it if someone would come over and play his daughter’s piano. When Larry McPherson (Tracy Letts) notices his son going for the same job he applied for, he straightens his tie and wishes him luck. When Father Leviatch notices Julie’s heartfelt, if slightly off-pitch, rendition of “Make Me a Channel of Your Peace” he casts her as the musical lead. When Gloria (America Ferrera) starts missing her little girl who’s turned into an angsty tween, Gloria’s love of their old games manifests through unusually detailed drawings.

When those drawings cause a rift in the portal between Barbieland and the real world, the differences between fiction and reality become messy. But it is that messiness which reveals so much not just about the Barbies, but Gloria and her daughter as well. The joy Jo feels at the end of Little Women would not have happened had she been the one to go to Europe instead of Amy. As Gerwig blurs the fiction and autobiographical nature of Alcott’s novel, we see how art and life reflect one another. In Lady Bird, the dreams of a flamboyant teenager to escape her hometown and go to the East Coast to experience culture only reveal how powerful the bonds of one’s home and upbringing are. All of these messy contradictions are a reality of life, and that is what Gerwig captures so beautifully. Her films are living, breathing works that invite an ongoing relationship with each one of them. As Gerwig said in her character of Frances over a decade ago: “And it’s funny and sad, but only because this life will end, and it’s this secret world that exists right there in public, unnoticed, that no one else knows about. It’s sort of like how they say that other dimensions exist all around us, but we don’t have the ability to perceive them. That’s—that’s what I want out of a relationship. Or just life, I guess.” That’s what my favorite movies depict, and why I can’t wait to see how Gerwig’s career unfolds.

Barbie

Year of release: 2023. Directed by Greta Gerwig. Starring Margot Robbie, Ryan Gosling, America Ferrera, Kate McKinnon, Will Ferrell, Michael Cera, and Helen Mirren.

If you saw the first teaser for Barbie, you may have thought the 2001: A Space Odyssey tribute was a one-off gag filmed just to promote the movie. You would have been wrong. Not to spoil the best surprises of the film, but the prologue telling the history of the world from the perspective of the Barbies is both hilarious and an ingenious homage to Kubrick’s masterpiece.

The homage is also thoroughly appropriate given the film’s epilogue where stereotypical Barbie (Margot Robbie) enters a new chapter of her life not at all dissimilar from man’s rebirth as the space child at the end of 2001. To drive the new life idea home, the final line is a funny zinger about the ability to do just that.

What if I also said there’s a “beach off” among the Kens that plays extremely similarly to the pie fight that initially ended Dr. Strangelove? Or a proud proclamation of the same dolls’ identities reminiscent of the most famous line from Spartacus? And what if in fighting the villain of patriarchy, two women communicate mentally, and one of their daughters refers to it as “shining?”

I am convinced there must be more Kubrick references in Barbie, and I’d happily see it again just to catch more of them, but the film delivers on so many other levels as well.

Gerwig and Baumbach’s story does almost nothing that I expected, and while the trailers hinted at similarities with The LEGO Movie, it is very much something different. When stereotypical Barbie discovers her perfect pink world with arched feet and hot, waterless showers falling apart with thoughts of *gasp* death, weird Barbie (Kate McKinnon) informs her she has to travel to the real world and find the child playing with her who has clearly become troubled by something, thus repairing the rift between their two worlds. Stereotypical Barbie just has to choose the Birkenstock over the pink heel, which to be fair, is a choice that not many Barbies would want to make.

If stereotypical Barbie is apprehensive about going to the real world, she is reassured when the other Barbies remind her that the invention of Barbie empowered young girls, letting them know they could be anything they want and not just mothers, and now as a result women hold all positions of power in the real world. And women everywhere will probably want to run up to her and hug her for initiating feminism and fixing all women’s problems.

“At least,” Helen Mirren’s narrator tells us, “That’s what the Barbies believe.” Helen Mirren also delivers my favorite joke in the film, turning an expected breakdown from Robbie’s Barbie into something hilarious, but I’m not spoiling that here.

The slap of cold water that is the real world shocks and appalls stereotypical Barbie while making Ken (Ryan Gosling) feel empowered and respected. A crash course on patriarchy thrills Ken, which he eagerly takes back to Barbieland to inform the other Kens on how they’re supposed to be subjugating the Barbies, riding horses, drinking beer, and watching The Godfather.

As an inverse of the real world’s patriarchal structure, Barbieland is a world where the Kens cannot be president, cannot have Supreme Court appointments, cannot hold high paying jobs, and exist purely for the edification of the Barbies. Since the Ken dolls were created by Mattel to be a companion for Barbie, it’s a very clever twist that demonstrates the toxicity of patriarchy that has plagued the real world for centuries. It reminds me of Aamer Rahman’s comedy bit about reverse racism only being possible with a time machine that would enable Africa to colonize Europe and inflict the abuses on white people that they inflicted on Black people for centuries.

I suppose it needs to be said given the absurd hatred Barbie is generating from right-wing incels for its wokeness, but a film that says we should build a society where women and men are treated equally with equal opportunities is hardly what I’d call woke. Although in a post-MAGA world, general human decency often is woke, so I suppose the label is not wrong, but the film’s basic feminist message is a beautiful thing that would have widely been accepted had not the alt-right gained so much traction in recent years. Nonetheless, the film’s box office success and glowing reviews are reason for hope.

Like Gerwig’s two previous films, Barbie is another example of Graham Greene’s maxim that movies should depict the world as it is and as it should be. While the subject matter here may seem far removed from Lady Bird and Little Women, there is a common thread of hope and decency that celebrates the beauty of love for what is true, noble, and good in the midst of an imperfect world.

Between Barbieland and the real world, there is so much good, and to the extent that the film has any villain at all, it is patriarchy. Patriarchy claims victims of the Kens, the Barbies, America Ferrera’s mother and secretary for Mattel, and Will Ferrell’s CEO of Mattel, who is not a villain copied from The LEGO Movie as the trailers suggested, but a well-meaning executive who wants to help girls and women while not realizing the ways he’s accepted patriarchal norms.

Ferrera’s third act speech that sets up the climax of the movie may be on-the-nose, but it exhibits the same passion a five-year-old girl has for her make-believe land with Barbies, and as a mom reconnecting with that same childhood passion, I thought the speech worked brilliantly.

Several reviews have commented on how Gosling steals the movie, but honestly, Robbie is just as good and gives him an equally clueless character to play off of. The two of them make for a great duo for a road trip movie that takes hundreds of unexpected turns.

Returning to Kubrick, Gerwig and Baumbach wrote a movie about human progress and relationships where our own inventions (patriarchy instead of HAL) plague us and hinder that progress until we can overcome them. It makes the 2001 framing story all the more fitting, and it shows how we can appreciate that journey through an obelisk and light show or a polarizing doll.

Personal recommendation: A-

Oppenheimer

Year of release: 2023. Directed by Christopher Nolan. Starring Cillian Murphy, Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, Florence Pugh, and Robert Downey Jr.

Bruce Wayne, as imagined by Christopher Nolan in his Dark Knight Trilogy, watches his parents be killed by a Gotham City gangster who turns out to have been hired by his later mentor Ra’s al Ghul. Bruce takes his childhood fear of bats and falling to create a superhero that visits those fears onto Gotham’s criminals. At the height of Bruce’s power, he builds a cellular spy network reminiscent of the Patriot Act to track his most dangerous nemesis, and he then takes the fall for that nemesis’ crimes to preserve peace in Gotham, laying aside his work as the caped crusader with feelings of guilt about whether he did the right thing.

Why I am talking about Nolan’s Batman? Because in the Nolan Cinematic Universe, J. Robert Oppenheimer is nearly indistinguishable from Bruce Wayne. Other than Wayne being a lapsed Episcopalian (commonly assumed knowledge among superhero fans) and Oppenheimer being Jewish. No comment on the casting of Cillian Murphy as a Jew.

I do not mean to sound glib or dismissive, but Oppenheimer, Nolan’s latest sprawling historical epic that plays with time and reckons with the potential end of the world, is essentially Batman Begins, The Dark Knight, and The Dark Knight Rises rolled into one three-hour film. That’s a factually neutral observation, not a criticism.

J. Robert Oppenheimer is a brilliant theorist who introduces quantum physics to the United States after studying it in Europe, alongside several Nazis. He’s selected to head the Manhattan Project, builds the first atomic bomb, later develops reservations about building more weapons of mass destruction although never expresses regret for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and then becomes a fall guy for the communist witch hunts under McCarthyism, all while being wracked by guilt over whether he destroyed or saved the world.

What makes Nolan’s presentation of this story engaging is the liberal cross-cutting from timeline to timeline, punctuating three phases of Oppenheimer’s career with comparisons to the other two. If the movie is too long (and it is by about 30 minutes), it’s never boring even as it becomes a relentless marathon of big ideas told with bigger gestures matched by Ludwig Göransson’s bombastic, swelling score.

As Oppenheimer, Murphy does a great job at capturing the stoic coldness typical of most Nolan protagonists. At their best (Christian Bale in The Prestige and Guy Pearce in Memento), Nolan protagonists are antiheros who meticulously construct their own hell through their obsession with their career or mission combined with their off-putting personalities. Oppenheimer is certainly no exception, burning bridges with authorities and fraternizing with communists, which includes screwing one, both of which combine to make his post-war crucifixion all the more of a foregone conclusion.

I was less interested in the kangaroo court that a political rival sets up to oust Oppenheimer as a petty act of revenge than I was in the film’s presentation of Oppenheimer’s willingness to go along with it over his guilt at starting the Cold War, or so he believes. If Bruce Wayne and Cooper (Interstellar) are Nolan’s most noble flawed protagonists, with Alfred and Leonard (The Prestige and Memento) being the most villainous ones, J. Robert Oppenheimer is somewhere in between. The common link is all these men obsess over something until they lose everything else.

Nolan is not a subtle filmmaker when it comes to political themes and philosophical ideas, as starkly contrasted by his masterful puzzle-making that provides easily missed clues, which build to a jaw dropping reveal. It’s why his best films are his ruthless revenge thrillers and his weakest are attempts at philosophizing and depicting a noble humanism. Oppenheimer has both elements, but it shifts back to the puzzle-making of his earlier films, and the philosophical ideas are less on the nose than they have been in other recent offerings of his.

The puzzle’s reveal and third act twist of Oppenheimer will be no shock to history buffs, but that doesn’t mean Nolan didn’t set them up masterfully. For those who don’t know who the villain is (I didn’t) I won’t spoil it here, but the performance by that actor is superb, and his reveal as evil and his downfall are masterfully handled. The downfall is slightly undermined by an on-the-nose moment when an intern reveals the senator who thwarted him was some kid from Massachusetts who wants to make a name for himself, “Kennedy. John F. Kennedy.”

For all of Oppenheimer’s masterful craftsmanship, it hits its viewers over the head with moments like that way too often. Some of them land the intended punch; some of them don’t. My favorite of such scenes was when Oppenheimer’s wife Kitty (Emily Blunt) is being grilled by Jason Clarke’s unethical lawyer and shows herself to be intellectually his equal if not superior. The most jarring of such scenes involves an interrogation about Oppenheimer’s ongoing affair with Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh) as Kitty imagines their naked bodies thrusting in front of her and the entire tribunal for the Atomic Energy Commission. It’s so obviously Nolan’s first explicit sex scene and one of the only scenes in the film not from Oppenheimer’s perspective, that it comes across as more of a clumsy shock than anything else.

Not that the sex scenes in Oppenheimer weren’t necessary for the story. They all contribute to Oppenheimer’s assholery, which is an essential part of a Nolan protagonist, and the first sex scene provides Nolan an opportunity to introduce Oppenheimer’s quote from the Bhagavad Gita, “Now I become death, the destroyer of worlds.” It’s another on the nose moment, especially given the line’s repetition when the Trinity test is successful, but for the integration of Oppenheimer’s messy personal life with his equal messy professional and political lives, I thought it worked.

As the theorist who can’t quite connect with the real world, Murphy’s Oppenheimer fits very neatly into the Nolan Cinematic Universe. As he struggles at school with how to relate to a professor, how to manage his affections for various women, how to serve his country, and whether the world should continue building atomic weapons, the gnawing loneliness of yet another genius man pervades the film. A tense, humorous exchange between Oppenheimer and General Groves (a very good Matt Damon) right before the Trinity test highlights that disconnect, as Oppenheimer assume the near zero chances of setting off a chain reaction that annihilates the entire world will appease the general. While we never see the horror of Oppenheimer’s work, Nolan does make it known through descriptions of the Japanese and Korean casualties as well as Murphy’s depiction of Oppenheimer’s breakdowns and imagining of his friends suffering the same fate.

At the center of the film is a tragedy, and rather horrific one at that, as Nolan’s lonely genius reaches out for connections in the most explosive ways possible finding the same hole that forms a link throughout so much of Nolan’s work.

Personal Recommendation: B

The Little Mermaid

Year of release: 2023 Directed by Rob Marshall. Starring Halle Bailey, Jacob Tremblay, Daveed Diggs, Awkwafina, Jonah Hauer-King, Javier Bardem, and Melissa McCarthy.

When the first teaser for Disney’s live action remake of The Little Mermaid dropped, the soundwaves surrounding it quickly became dominated by racist morons complaining that Ariel was no longer white with red hair. A part of me can’t believes I had to type that sentence in 2023, but here we are. What that toxic discourse covered up was how bad the teaser looked. I’m cynical enough to think Disney would not be above starting such racist bullshit as a marketing ploy, but regardless, the first focus on the film was the casting of Halle Bailey.

For the record, she is phenomenal and probably the best live action Disney princess to date. She’s substantially better than Emma Watson as Belle in the Beauty and the Beast remake, partially because her singing isn’t autotuned into oblivion, and partially because she captures the longing of a teenage mermaid for the unknown human world quite well. I look forward to seeing her in the adaptation of The Color Purple musical in December. It is also very nice to see a Disney princess and mythological creature portrayed as a person of color, and Disney and Rob Marshall deserve credit for her casting.

What Disney does not deserve credit for is the ableist rewriting of Howard Ashman’s lyrics. (Also the straightening of them, but more on that later.) In “Kiss the Girl” Lin-Manuel Miranda provides some “sanitized” words that stand out like a sore thumb, because apparently Disney executives correctly realized it was predatory to kiss a girl who can’t consent, but erroneously decided Ariel couldn’t consent because she can’t speak at that moment.

I’m very sorry to hear that executive at Disney are so out of touch with reality that they are unaware that sign language, gesturing, writing, and other forms of non-verbal communication exist. And that they seem to think that people who cannot speak are broken, inferior beings who can’t fall in love or express that. To make matters worse, Ursula erases Ariel’s memory so she doesn’t realize she needs to share true love’s kiss with Eric before three days or she reverts to a mermaid. For the supposed awareness around consent, that deviation from the original makes Sebastian, Flounder, and Scuttle’s forcing of the romance far more cringeworthy than anything in Ashman’s original lyrics.

As to why that deviation from the original film was added to a movie that mostly adheres to the original slavishly, I don’t know. It might be explained by the bloat that permeates the entire movie. Rob Marshall’s overriding attitude seemed to be “Why do something in two minutes, if you can do it in eight?” The only thing Ursula’s memory erasure does is add extra dialogue making the on-land romance between Ariel and Eric take longer.

At just over two hours, the movie is unquestionably too long. The first hour of it moves along passably, with “Under the Sea” being the one scene that doesn’t look like it was shot by a camera with a black nylon stocking over it. It is the best song in the score, and it deservedly won Menken and Ashman their first Oscar in 1990. Daveed Diggs was a fantastic choice to play Sebastian, and he delivers it beautifully. Marshall’s cutting to a school of dolphins for “down here all the fish is happy” was a bizarre choice, as the emphasis on the word “fish” with the imagery of dolphins took me right out of the song, but Diggs pulled me back in quickly, in spite of some other visual choices on Marshall’s part that make no sense.

Excuse me, but I need to get this out of the way.

THEY CUT THE BEST VERSE OF “POOR UNFORTUNATE SOULS!!!!!!!!” LIKE, WHAT THE ACTUAL FUCK WERE THEY THINKING WITH THAT??????

Okay, now on to the moment where the movie really began to derail. Melissa McCarthy is fine as Ursula. She’s no where near as menacing or flamboyantly queer as Pat Carroll’s Sea Witch was, but I really don’t think that’s her fault. Her first two scenes before her big number are almost verbatim quotes of Carroll’s lines, which pales for anyone who enjoyed Carroll’s delivery.

More problematically, Marshall’s odd visual choices really came to a head in “Poor Unfortunate Souls.” When Ursula sings “Now it’s happened once or twice, someone couldn’t pay the price” she shows two merfolk being punished in the animated film. Here she holds up eight skulls of merfolk, which is substantially more than once or twice. The relentlessly dark palette of the film is probably most offensive in this song, with the dark blue being punctuated by bursts of orange, which is so uninspired color-wise that it’s depressing.

Even more problematically, the missing verse is the one about communicating without words and saying women are better silent anyway. Apparently the filmmakers decided a villain giving villainous advice was a problem, so they stripped the villain of some of her most iconic lines, which contribute to “Poor Unfortunate Souls” being the best Disney villain song. (Yes, I will die on that hill. Don’t argue that with me.) The other problem with omitting that verse is that the lyric and dramatic foil that Ashman set up between “Poor Unfortunate Souls” and Ariel’s wish in “Part of Your World” is gone too.

Ariel sings, “Bet you on land they understand, bet they don’t reprimand their daughters.” When Ursula sings, “Yes, on land it’s much preferred for ladies not to say a word, after all, dear, what is idle prattle for?” it not only shows the Sea Witch is subverting Ariel’s dreams while pretending to answer them, but it also forms a dramatic development through the song lyrics. Cutting that was honestly unforgivable.

One of the best aspects of the Disney renaissance was the way almost all the villains resurrected the queer coding of the 1940s and ‘50s. Pat Carroll’s butch, drag queen-inspired Sea Witch, has obvious lesbian undertones, of which McCarthy’s Ursula only has a faint reminiscence. The new revelation that Ursula is King Triton’s sister contributes to the straightening of the character by making her an evil aunt of the protagonist and not the flamboyant outsider she was in the 1989 film. The makeup copies the animated character, so the queerness is still there minimally, but the desire to control and manipulate a young woman is gone along with the missing verse of the villain song. This Ursula is only a power-hungry witch willing to use her niece as a pawn; the predatory and sexual undertones are eradicated.

Releasing The Little Mermaid on the last weekend before Pride Month, with its cuts and alterations to the lyrics of an iconic gay song-writer who died from AIDS was certainly a choice. That his song-writing partner had to write new songs that drastically pale in comparison to the work that largely started the Disney renaissance adds insult to injury.

For the record, I will also die on the hill that Alan Menken has never partnered with a lyricist as great as Howard Ashman. Steven Schwartz came close, but everyone else Menken has worked with is a notable step down. Menken and Miranda have written three new songs for this version of The Little Mermaid. Eric’s solo, “Wild Uncharted Waters,” is fine, even if it garners a deserved eyeroll for its introduction of on-the-nose similarities between Eric and Ariel by making them both rebellious teenagers from their opposite sex parents.

“The Scuttlebutt” is a fifth-rate Hamilton remix and an affront to humanity that is so jarringly different from the rest of the score that it feels like a painful slap in the face reminding us that Ashman died and Miranda does not even have half of his talent.

Ariel has one new solo, “For the First Time,” which makes no freaking sense at all. I am willing to overlook giving Ariel a song after she loses her voice and is supposed to be mute until she breaks Ursula’s necklace, since she can obviously still think. However, the lyrics are all about adapting to life on land, how difficult it is to walk because of gravity, how hard it is to wear a corset, and how uncomfortable shoes are. I’m sorry, but if Ariel still thinks a fork is a dinglehopper and you use it to style your hair, how the hell does she know what gravity, corsets, and shoes are, and how could she be singing about them? It would be as if Eliza Doolittle, after mastering the speech inflections of a British lady, sang a song about attending a ball and how wonderful it was without ever having been to a ball.

“Part of Your World” was an I want song that was largely responsible for launching the Disney renaissance. “Under the Sea” cemented it as a fabulous show-stopper, and “Poor Unfortunate Souls” made a clichéd villain a menacing, three-dimensional character while giving representation to the LGBTQ+ community at the height of AIDS. Nowadays Disney is largely devoid of original ideas, and while their desperate cash grabs usually have enough great material from their source to be watchable, they’re a far cry from the original that many people loved.

For the record, I never loved The Little Mermaid. I adore the score and might argue it’s the best work Menken and Ashman did for Disney—it’s really close between that and Beauty and the Beast—but the absurd happy ending that contradicts Hans Christen Andersen’s tragic fairy tale of longing for unattainable love was a weak point for me as soon as I was aware of it. There was a brief moment in the 2023 Little Mermaid when I thought a quasi-tragic ending might actually occur. (If it had occurred, I’d have written a very different review.) Unfortunately, Disney is afraid to take any risks and do anything that would alter the products they built their name on.

Around half-way through this movie, I felt bad for Halle Bailey. She was cast as a Disney princess, gave it her very, very good all, only to be stuck in a lifeless cash grab that bastardized the best aspects of the original film. I even felt a little bad for Rob Marshall, because most of the lousy creative decisions obviously came from higher up executives.

Ultimately, I was angry and sad to watch an iconic queer-coded character neutered, to watch a famous gay lyricist have his lyrics likewise neutered, and to watch yet another bloated, soulless remake from Disney that neuters the story of a gay author writing about his forbidden love who married a woman leaving him alone. If Disney wants to neuter anything as a force for good, perhaps they could neuter the careers of racist and homophobic fascists like Ron DeSantis and Trump instead of churning out remakes like this.

Personal Recommendation: D