Archive for January, 2015

American Sniper

Posted by Evan in Uncategorized on January 22, 2015

Year of Release: 2015 Directed by Clint Eastwood. Starring Bradley Cooper, Sienna Miller, Sammy Sheik, and Keir O’Donnell.

It is always unfortunate when a film generates such strong political reactions that those reactions dominate any discussion of the film. Such reactions make it difficult to discuss the film and its merits without first addressing the controversy. I must admit I’m baffled disappointed to see the intense politicized responses American Sniper is receiving because it supposedly celebrates the Iraq war and glorifies a man who may have been a war hero, but was apparently less than a role model in real life. I think that in calling the film a straightforward defense of the Iraq war, critics are seriously undermining the film’s strengths and selling short its sense of conflict and its depiction of the tragic effects of the war and a career dominated by violence.

In his four tours of duty during the Iraq War, Navy SEAL Chris Kyle (a very good Bradley Cooper) is credited with 160 kills out of a probable 255, and he feels confident that every shot he took was the right thing to do. Kyle, having a penchant for violence, is eager to join the army, fight for his country, and kill those damn terrorists. Having hunted all his life he is a natural sniper, and he soon becomes a hero to his fellow soldiers who feel safe when he is overseeing them. American Sniper is the story of a very pro-war, pro-gun soldier, and thus, it makes total sense that the Iraq War is accepted as something that happened. Just because the film depicts the war without questioning its wisdom or lack thereof, does not mean the film glorifies the war or condemns it. American Sniper is neither pro-war nor anti-war; it is just war.

More importantly, there are many scenes which show the tragic effects and heavy toll of both the war and Kyle’s many killings. I really do not understand how someone could watch the scenes between Kyle and his wife, his son, and his colleagues and call the film unapologetically pro-war. When Kyle takes his wife for her prenatal checkup, his resting blood pressure is 170 over 110. He screams at a nurse who does not respond to his crying daughter quickly enough. He is unable to accept a complement from a marine when he is out with his son. The breakdown he has at a child’s birthday party is very painful to watch. To call the film a celebration of the Iraq war is to badly sell those scenes short.

American Sniper undoubtedly has some pacing problems, and there are a couple miscalculated subplots which should either have been removed or developed into much larger segments. The standoff/manhunt between Kyle and rival Iraqi sniper Mustafa (Sammy Sheik) plays too much like a conventional thriller, and the half-baked attempts to set up a rivalry between them would only have worked if Mustafa had been given much more back story. As it is, the scenes of him hunting Kyle distract from the story and make it too obvious how their standoff will eventually end. The resolution of that subplot is the film’s weakest moment, because it is handled like a triumphant moment out of a mediocre Marvel movie.

I also wish the final twenty minutes had been developed into a full hour. There is rich, poignant material in that section concerning PTSD, guilt, adjusting to a quiet life after being one of the deadliest SEALs, and one’s duty as a husband and father. While some scenes do capture the tension, raging emotions, and painful consequences, as a whole that part of the story is rushed through too quickly.

As a point of comparison, when Francis Ford Coppola was asked to write the screenplay for Patton, his first thought was, “Oh crap. Half the country loves him because they think he won the war, and half the country hates him because they think he was a sadistic war criminal. If I chose either side, I’ll alienate half my audience.” He chose to respect both sides, portraying Patton as a brilliant general who loses his temper and gives in to nasty violence, a conflicted character who too often gives into his violent nature but still has a strong sense of dignity. Jason Hall did something similar with his script for American Sniper. He does not shy away from portraying Kyle’s violence and even showing it to be at times successful, but he also portrays a damaged human being whose choices harm not only on himself but his family as well. The scene when Kyle’s brother (Keir O’Donnell ) makes a disparaging comment about the war, only to have Kyle look at him as if he were a stranger is a particularly acute example.

Kyle’s first kill, which opens the film, is another powerful example of the cost of violence. As a mother hands her son a grenade, Kyle hesitates to shoot. It is the first scene, we have no context, and this a perfect textbook example of self-defense. Taking the shot seems like a no-brainer. Before Kyle pulls the trigger, there is a half hour flashback to his childhood and training, showing him bonding with his equally violent father, protecting his little brother, grieving on 9/11, and flirting with his wife-to-be (Sienna Miller). After witnessing the hardships and joys of Kyle’s life, when the film returns to Iraq, his hesitation is perfectly natural, and the tragic evil of deliberately ending any life is fully dramatized.

Finally, if anyone doubts Eastwood’s stance on violence, remember, he wrote and directed this:

Content Advisory: Some brutal wartime violence, disturbing gory images, profane and obscene language throughout, intense themes of PTSD and family discord, and mildly sensual foreplay. MPAA rating: R

Suggested Audience: Adults

Personal Recommendation: B-

2014 Top Ten

Posted by Evan in Uncategorized on January 10, 2015

Updated 2/25/15 to include A Most Violent Year. Snowpiercer was dropped from #20 as a result.

I don’t have a hard fast rule about eligibility. The purpose of a yearend list is to highlight the films that I found most rewarding over the past year, not document which year a film was released. I made a pretty good effort this year than last to track down my most anticipated films in time for this list, but I’m sure there are still some great films which I missed. I have highest hopes for Force Majeure, Beginning with the End, Siddharth, Virunga, and The Strange Little Cat.

In addition to a top ten, I’m also including five runners up, and five honorable mentions.

As a necessary disclaimer, just because these films from last year that meant the most to me, does not mean I necessarily recommend them. If you think any of them sound like something you might like, research them and make an informed decisions. And with that, onto the lists:

Honorable Mentions:

20. Edge of Tomorrow (Doug Lima)

19. Blue Ruin (Jeremy Saulnier)

18. As It Is in Heaven (Joshua Overbay)

17. The Sublime and Beautiful (Blake Robbins)

16. A Most Violent Year (J. C. Chandor)

Runners-up:

15. Inherent Vice (Paul Thomas Anderson) – There’s almost no one to whom I’d recommend this; the plot is a semi-incoherent mess, and the story itself is more than a little disturbing, but that’s basically the point of this neo-noir comedy, in which the hippie, stoner private eye “Doc” (Joaquin Phoenix) finds himself in the midst of an increasingly convoluted, dangerous mystery in which everyone seems to want his help for different reasons, but the Doc is just as lost as his clients.

14. Birdman or: (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) (Alejandro González Iñárritu) – An aging Hollywood star (Michael Keaton) tries to prove his relevance by conquering the Great White Way, and amidst disastrous rehearsals, the messy backstage life of actors raises interesting questions as to whether these foolish conceited actors have any insight to offer. Carefully edited to appear as a single take live performance, Birdman will likely either enthrall or infuriate you. (full review)

13. Noah (Darren Aronofsky) – Not everything works – the film stumbles a bit once onboard the ark – but Aronofsky’s vision of the antediluvian world is fantastic to behold, and his interpretation of the story of Noah adds new depth and insight to one of the oldest stories about the consequences of original sin. (full review)

12. Selma (Ava DuVernay) – A powerful dramatization of Martin Luther King Jr.’s march from Selma to Montgomery, as well as the dynamics between King, his family, his friends, and politicians. Especially touching are the scenes between David Oyelowo (King) and Carmen Ejogo (his wife Coretta). Portraying real, flawed human beings and their struggles, Selma is not one to miss.

11. A Most Wanted Man (Anton Corbijn) – A sleek espionage thriller helmed by great performances, especially from the late Philip Seymour Hoffman, this adaptation of John le Carré’s novel is surprisingly effective and unnerving.

The Top Ten

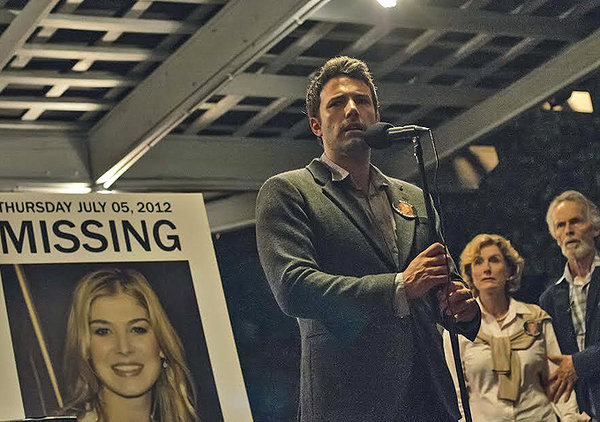

10. Gone Girl – I haven’t always been the biggest fan of David Fincher, but Gone Girl may be changing my mind. Combining several Hitchcockian elements with biting dark satire, Fincher’s latest film is a brutal exposé of obsession with appearances, media manipulation, maintaining fake personas, and the public’s gullibility. When amazing Amy (Rosamund Pike) disappears on her fifth wedding anniversary, passive husband Nick (Ben Affleck) finds himself the chief suspect in the subsequent police investigation. Featuring two antiheroes (not one, as some reviews have said) and a psychopathic protagonist, Gone Girl deliberately plays into the nastiest examples of sexism in order to expose just how shallow and absurd they are. (a lengthy, spoiler filled discussion here)

9. The Immigrant – Beautifully tinted with sepia tones, The Immigrant immediately sets up an haunting contrast with the cold brutal world of 1920’s New York that Polish immigrant Ewa (Marion Cotillard) arrives in. Looking for work to help her sister, she is exploited by the pimp Bruno (Joaquin Phoenix) who will do anything for his own survival even as he suffers flickers of conscience due to his cruel treatment of Ewa. Director James Gray expertly frames each scene, and with careful pacing and subtle foreshadowing throughout, all of the film masterfully comes together for a powerful, thought-provoking finale indicating that there is often much depth beyond mere surface appearances.

8. The LEGO Movie – Containing references to Star Wars, The Matrix, The Dark Knight, Toy Story, The Incredibles, and Buster Keaton’s The General to name a few, Phil Lord and Christopher Miller’s witty and hilariously self-aware parody of and tribute to blockbuster entertainment is undoubtedly this year’s biggest surprise. Not just an exciting adventure story for children, The LEGO Movie deconstructs the standard tropes of many superhero and kids movies with lines like, “Always follow your intuition…unless your intuition is terrible.” It also emphasizes the importance of fantasy and creativity as a way which children learn. Indeed, everything is awesome.

7. Ida – When a young woman about to take her vows to be a nun learns of her family’s dark history, her entire world is shaken and she undergoes a crisis of identity. Embarking on a journey with her aunt, she uncovers painful secrets which test her resolve and remind the viewer that nothing should be taken for granted. Director Pawel Pawlikowski frames each shot with stunning precision, and his use of still camera and a full screen aspect ratio creates the sensation of a window into a world and even into a soul. (full review)

6. Begin Again – This is a heartfelt story of second chances in which a song really does save several people’s lives. As drunk, washed up music producer Dan, Mark Ruffalo is very likeable and as Greta, a down and out songwriter, Keira Knightley effortlessly shines. The two meet in bar and decide to record an album outdoors in New York City. Eschewing Hollywood clichés, Once director John Carney crafts another story about a once in a lifetime opportunity for decent, empathetic human beings to pursue their art and make something unique and magical with it. There is no tense drama or overblown indecision, but rather quiet moments of grace and generosity that are touching and inspiring in their direct simplicity. (full review)

5. Only Lovers Left Alive – Jim Jarmusch’s moody rumination on desire, temperance, art, its place in society, and eternity is beautifully realized in the story of two vampires: the melancholic perfectionist Adam (Tom Hiddleston) and the knowledgeable, pragmatic Eve (Tilda Swinton). Cursed to destructively feed on others throughout eternity, their search for beauty and great art is threatened by the increasingly prevalent mediocrity that supplants excellence as well as the carelessness, drugs, and pollution of the last couple decades, which has poisoned much of their blood supply. The vampires’ need for blood acts as a metaphor, suggesting we need to be careful what we consume; bad art and good art affects and influences us, and allowing mediocrity to permeate soon makes bad art (blood) more prevalent. Only Lovers Left Alive recognizes the power of art’s influence on a culture as well as the tragedy of its destruction.

4. The Grand Budapest Hotel – (modified from a review published here) The second film on the list to utilize full screen framing, Wes Anderson’s latest film is as whimsical and eccentric as to be expected, but this story of nostalgia for a fantasy world of secret societies, crazy hijinks, unattainable goals, murder mysteries, and above all, friendships is rife with bittersweet humor and surprising poignancy. As the concierge of the titular hotel Ralph Fiennes effortlessly captures the typical self-centered deadpan of Anderson protagonists as well as a longing for something beyond this imperfect world. Told through the eyes of Zero (Tony Revolori), the devoted lobby boy of the Grand Budapest, the film chronicles the final glory days of a time and a world long since past.

3. The Babadook – (originally published here) The festering of grief and the frightening ways such grief manifests itself is at the heart of The Babadook, director Jennifer Kent’s horror film about the relationship between a mother and her son. Amelia (Essie Davis) has never really accepted her husband’s death, which occurred as he drove her to the hospital to deliver their son Samuel (Noah Wiseman). With Sam’s seventh birthday approaching, Amelia is feeling increasingly overwrought, and she copes by isolating herself and Sam in their gloomy Victorian home, making an ideal setup for Mister Babadook, a sinister popup book character, to come knocking. Despite their misguided choices, neither Amelia nor Sam ever loses our sympathy. Kent expertly plays upon the audience’s sympathies and fears, reminding us of the beauty of the love between a parent and a child and the tragedy that occurs when it is threatened. (full review)

2. Two Days, One Night – The Dardenne brothers have crafted what may be their finest film to date. When Sandra (a phenomenal Marion Cotillard) loses her job after her coworkers vote for a bonus which entails her being fired, she persuades her boss to hold a second ballot, and she will have the weekend (two days and one night) to persuade her coworkers to vote for her to stay. Each encounter with her coworkers is filmed with increasing drama and tension, and the film never demonizes anyone as it emphasizes the dignity of work and the human person. Best of all, when you think the movie has to end one of two ways, falling on one side or another, the Dardennes find a third way that logically and incredibly ties everything together and finds quiet moral triumph in putting up a good fight.

1. Into the Woods – Admittedly, I am one of the world’s biggest Stephen Sondheim fans, but Rob Marshall’s adaptation of the Tony award winning 1987 musical is a lovingly crafted, faithful adaptation that preserves the essence of Sondheim and James Lapine’s story about being careful what you wish for and the far reaching consequences of our wishes that often go well beyond what we can imagine. With a fantastic score and an all-around great cast, Into the Woods is a delight from the first frame to the last. (full review)

Into the Woods and Moral Relativism

Posted by Evan in Uncategorized on January 3, 2015

Major SPOILERS for Into the Woods. Don’t read if you don’t know the story and don’t want it spoiled.

I have seen several reviews of Into the Woods which suggest the recent adaptation of Sondheim and Lapine’s musical is a defense of moral relativism, the heresy that there is no absolute truth and we get to decide what is right and wrong for ourselves. One manifestation of relativism is that the determining factor for morality is our intentions, or the widely beloved belief that the ends justify the means. I find this slightly ironic, because I believe Into the Woods is actually a pretty strong critique of relativism.

On one level, I will admit that concluding that Into the Woods, or more specifically one song of Into the Woods, promotes moral relativism is not completely illogical. Towards the end of the musical, after several characters have died, adultery has been committed, and a giant is raging through the kingdom, the two children, Jack and Little Red Riding Hood, are very confused about what is right and wrong, and they turn to the two remaining adults, Cinderella and the Baker, for guidance. At this point, Cinderella and the Baker sing one of the most beautiful songs in the show, “No One is Alone.”

The lyrics of “No One is Alone” that are causing concern are:

“You decide what’s good,

You decide alone…Wrong things, right things…

Who can say what’s true…Witches can be right,

Giants can be good,

You decide what’s right,

You decide what’s good.”

I concede if you look at just those lyrics, concluding Into the Woods is a dark, morally relativistic revision of fairytales is semi-defensible. However, to conclude that based on those lyrics, you would have to ignore not only the other lyrics of “No One is Alone,” but also the entire story which has preceded the song.

First allow me to put the above lyrics into context:

“You decide what’s good,

You decide alone,

But no one is alone.”

Right there, Sondheim is setting up a paradox. The characters are singing that they have to decide alone, for themselves, what is right and wrong, but the next line says they are not alone, so obviously their moral decisions are not going be made solely on their intentions. You cannot decide alone, if you are not alone.

“Mother isn’t here now,

Wrong things, right things,

Who knows what she’d say?

Who can say what’s true?

Nothing’s quite so clear now

Do things, fight things,

Feel you’ve lost your way?

You decide,

But you are not alone.”

The key line from this passage is “Nothing’s quite so clear now.” That does not mean there is no objective right and wrong. It means the characters are scared and confused as to what is right. This song is sung at the end of the story. As I said above, by this point the characters have strayed from the path, made many foolish and selfish decisions, and they are about to kill a giant. This is the first time that these characters have done any introspection, and in thinking about their past choices, they now feel remorse and are unsure if the decisions they have made and will make are morally right.

“Witches can be right,

Giants can be good,

You decide what’s right,

You decide what’s good.

Just remember:

Someone is on your side,

Our side—

Someone else is not.

While we’re seeing our side—

Maybe we forgot:

They are not alone.

No one is alone.”

The entire musical is about characters who decide what’s right for themselves, and as a result create the huge mess they are in at the end. They realize that the Witch was not wrong when she accused them of being petty and selfish. The giant may not have been as evil as they thought. And then these morally flawed characters give the best advice they can think of: remember you’re not alone and your actions affect everyone, and even though you may feel alone, in making any important decision remember not to think of just yourself.

In a song that was unfortunately cut from the film, the Baker’s Wife sings:

“If the thing you do is pure in intent,

If it’s meant,

And it’s just a little bent,

Does it matter?

No, what matters is everyone tells tiny lies

What’s important really is the size…

When the end’s in sight you’ll realize,

If the end is right, it justifies the beans!”

The Baker’s Wife sings this at the height of her ruthless, do whatever it takes to lift the spell mentality. Emily Blunt portrays that mentality very well in her arguments with James Corden, so I can understand cutting the song, even though I wish it had been kept to make the moral even clearer. After that song, the Baker’s Wife forces the magic beans on other characters, and as a result the second beanstalk grows, which leads to the giant coming down to look for Jack and killing the Baker’s Wife while the giant crashes through the woods. That song portrays the clearest example of relativism, the belief that the ends justify the means, as leading to a character’s death. It hardly seems likely that the musical would contradict itself with its penultimate number.

I said this in my review, but I think it bears repeating. The dramatic climax of the musical, is “The Last Midnight” when the Witch, disgusted with the selfishness and rationalization she is witnessing, places her final curse on the characters.

“Told a little lie,

Stole a little gold,

Broke a little vow,

Did you?

Had to get your prince,

Had to get your cow,

Have to get your wish,

Doesn’t matter how—

Anyway, it doesn’t matter now.”

The entire point of Into the Woods is that all those actions were wrong, and the characters must reap the consequences. “No One is Alone” is spurred by the guilt they feel from the Witch’s accusations. I would not disagree that some lyrics of “No One is Alone” demonstrate that the characters are still attached to their selfishness and relativism, but moral awakening is slow, and the song is a big step in the right direction for them.

Finally, “No One is Alone” happens during the story. That means it is not the moral pronouncement common at the end of a fairytale; it is the opinion of the characters singing it, and those characters are imperfect people struggling to do their best. The following song, “Children Will Listen,” takes place outside of the story, and that song presents the moral of this fairytale. The moral of Into the Woods is: careful what you do and say, because children will listen and learn. Or, in other words, our actions have consequences, and while straying from the path (i.e. sinning) is an inevitable part of our nature, we should always remember our sins affect everyone, not just ourselves.

Is that the makings of a subversive musical that promotes relativism? I think obviously not. Into the Woods may be subversive, and it certainly deconstructs fairytales to undermine the traditional notion of “happily ever after,” but in doing so, it shows a keen moral awareness and strong critique of a prevalent heresy. And in conclusion:

The way is dark,

The light is dim,

But now there’s you,

Me, her, and him.

The chances look small,

The choices look grim,

But everything you learn there

Will help when you return there.

The light is getting dimmer,

I think I see a glimmer—Into the woods, you have to grope,

But that’s the way you learn to cope,

Into the woods to find there’s hope

Of getting through the journey.